Tibetan people

|

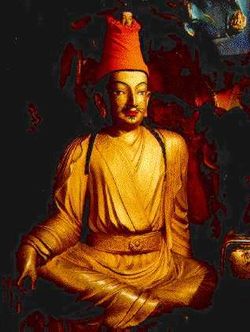

| (1st row) Songtsän Gampo • 1st Dalai Lama • 10th Panchen Lama (2nd row) Jamphel Yeshe Gyaltsen • Tsarong • Mipham Chokyi Lodro (3rd row) Sogyal Rinpoche • Alan Dawa Dolma • Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme |

| Total population |

|---|

| 5.4 million |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Tibet Autonomous Region, and parts of Qinghai, Sichuan and Gansu provinces of |

| Languages |

|

Tibetan, Rgyalrong, Baima language (bqh), Muya language (mvm), Mandarin, Hindi |

| Religion |

|

Predominantly Tibetan Buddhism, Bön |

| Related ethnic groups |

The Tibetan people (Tibetan: བོད་པ།; Chinese: 藏族; pinyin: Zàng Zú) are indigenous to Tibet and surrounding areas stretching from Central Asia in the North and West to Myanmar and China Proper in the East and India, Nepal and Bhutan to the south. Numbering 5.4 million, they are the 10th largest of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by the People's Republic of China.

Contents |

Demographics

As of 2008, there are 5.4 million Tibetans in China.[1] The SIL Ethnologue in 2009 documents an additional 189,000 Tibetan language speakers living in India, 5,280 in Nepal, and 4,800 in Bhutan.[2] The TGIE's own refugee register counts 145,150 Tibetans outside Tibet: a little over 100,000 in India; in Nepal there are over 16,000; over 1,800 in Bhutan and more than 25,000 in other parts of the world. Tibetan communities are present in the USA, Canada, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, France, Taiwan, Australia, Mexico and Costa Rica.

How the current numbers compare to Tibetans historically is a difficult claim. The Tibetan Government in Exile (TGIE) claims that the 5.4 million number is a decrease from 6.3 million in 1959[3] while the Chinese government claims that it is an increase from 2.7 million in 1954.[4] However, the question depends on the definition and extent of "Tibet"; the region claimed by the TGIE is more expansive and China more diminutive. Also, the Tibetan government did not take a formal census of its territory in the 1950s; the numbers provided by the government at the time were "based on informed guesswork".[5]

The Tibetan population growth is attributed by PRC officials to the improved quality of health and lifestyle of the average Tibetan since the beginning of reforms under the Chinese governance. According to Chinese sources, the infant mortality rate in Tibet was 35.3 per 1,000 in the year 2000, as compared to the 430 infant deaths per 1,000 in 1951. The average life expectancy for Tibetans rose from 35 years in 1950s to over 65 years in the 2000s.[6] Infant mortality in China as a whole was officially rated as 3.1 percent in 2003. UNICEF in 2004 acknowledged the improvements but said that the the infant mortality rate still lags behind the national rate eightfold, although Melvyn Goldstein and his colleagues in 2002 reported a 12.9% rate (fourfold), and official sources in 2004 rated it 3.1% (about equal).[7]

Language

The Tibetan language encompasses many dialects. Khampas have several Kham language dialects which may be unintelligible to Amdowas, and the Lhasa dialect may be unintelligible to both of those groups.[8]

Physical adaptation to high altitudes

The Tibet Paleolithic Project is studying the Stone Age colonization of the plateau, hoping to gain insight into human adaptability in general and the cultural strategies the Tibetans developed as they learned to survive in this harsh environment.

The ability of Tibetans to function normally in the oxygen-deficient atmosphere at high altitudes - frequently above 4,400 metres (14,400 ft), has often puzzled observers. Recent research[9][10][11][12] shows that, although Tibetans living at high altitudes have no more oxygen in their blood than other people, they have 10 times more nitric oxide and double the forearm blood flow of low-altitude dwellers. Nitric oxide causes dilation of blood vessels allowing blood to flow more freely to the extremities and aids the release of oxygen to tissues. What is not yet known is whether the high levels of nitric oxide are due to a genetic mutation or whether people from lower altitudes would gradually adapt similarly after living for prolonged periods at high altitudes.

Origins

Genetics

One 2010 study, part of the 1000 Genomes Project and published in the journal Science,[13] showed that modern Tibetans split off from the Han less than 3,000 years ago.[14] However, archaeologists say they believe that the Tibetan plateau has been inhabited for at least 7,000 years and maybe for as long as 21,000 years. "The separation of Tibetans and Hans at 3,000 years ago is simply not tenable by anything we know from the historical, archaeological or linguistic record," said Mark Aldenderfer, a Tibetan expert at the University of California, Merced.[15] Aldenderfer also noted there had probably been many migrations onto the Tibetan plateau, and that there was indirect evidence that pastoralists had entered the plateau from the north-northeast around 6,000 years ago. Earlier genetic studies have found that Tibetans are more similar to northern Han than to those from southern China, and have some admixture of genes from Central Asia, he said. Geneticists have a more elastic view of dates than do archaeologists, and the estimate of a Han-Tibetan population split at 3,000 years ago could probably have been adjusted to 6,000 if the geneticists had taken any account of any other kind of evidence.[15]

The distribution of Haplogroup D-M174 is found among nearly all the populations of Central Asia and Northeast Asia south of the Russian border, although generally at a low frequency of 2% or less. A dramatic spike in the frequency of D-M174 occurs as one approaches the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of western China. D-M174 is also found at high frequencies in Japan but it fades into low frequencies in the Han populated mainland China between Japan and Tibet.

Stein observes:[16]

Different racial types live side by side or coalesce. The predominant strain in most cases in Mongoloid, but many travellers have been struck by the prevalence of what they describe as a 'Red Indian' type (in Kongpo, among the Hor nomads, and in Tatsienlu). Others have noted a European, 'Hellenic' or Caucasian element which seems sometimes to be identical with the preceding type, and sometimes to denote a separate type altogether, especially in north-eastern Tibet. A dwarfish type occurs in Chala, a district of Kham. Though all these are but impressions, the fact that different groups exist is plain. According to travellers with no special claim to scientific knowledge, the brachycephalic type predominates in the farming communities of the Brahmaputra valley and in the south-east. In Ladakh, it would appear to have been superimposed on a dolichocephalic strain (no doubt Dards). Northerners, as in the Changthang lakes region—the Hor and Golok people—are themselves dolichocephalic , on the other hand. However, anthropologists merely distinguish two types: one distinctly Mongoloid and of slight build, typical of Kham. Blue-eyed 'blond' types have also been observed in the north-east.

The romantic claim that American Hopi and Tibetans are related has not found support in genetic studies. Some light has been shed on their origins, however, by one genetic study[17] in which it was indicated that Tibetan Y-chromosomes had multiple origins, one from Central Asia while the other from East Asia.

Traditional explanation

Tibetans traditionally explain their own origins as rooted in the marriage of the monkey Pha Trelgen Changchup Sempa and rock ogress Ma Drag Sinmo.[18] Tibetans who display compassion, moderation, intelligence, and wisdom are said to take after their fathers, while Tibetans who are "red-faced, fond of sinful pursuits, and very stubborn" are said to take after their mothers.

Religion

Most Tibetans generally observe Tibetan Buddhism or a collection of native traditions known as Bön (also absorbed into mainstream Tibetan Buddhism). There is also a minority Tibetan Muslim population.

Legend said that the 28th king of Tibet, Lhatotori Nyentsen, dreamed of a sacred treasure falling from heaven, which contained a Buddhist sutra, mantras, and religious objects. However, because the Tibetan script had not been invented, the text could not be translated in writing and no one initially knew what was written in the it. Buddhism did not take root in Tibet until the reign of Songtsen Gampo, who married two Buddhist princesses, Bhrikuti and Wencheng. It then gained popularity when Padmasambhāva visited Tibet at the invitation of the 38th Tibetan king, Trisong Deutson.

Today, one can see Tibetans placing Mani stones prominently in public places. Tibetan lamas, both Buddhist and Bön, play a major role in the lives of the Tibetan people, conducting religious ceremonies and taking care of the monasteries. Pilgrims plant prayer flags over sacred grounds as a symbol of good luck.

The prayer wheel is a means of simulating chant of a mantra by physically revolving the object several times in a clockwise direction. It is widely seen among Tibetan people. In order not to desecrate religious artifacts such as Stupas, mani stones, and Gompas, Tibetan Buddhists walk around them in a clockwise direction, although the reverse direction is true for Bön. Tibetan Buddhists chant the prayer "Om mani padme hum", while the practitioners of Bön chant "Om matri muye sale du".

Culture

Tibet boasts a rich culture. Tibetan festivals such as Losar, Shoton, Linka (festival), and the Bathing Festival are deeply rooted in indigenous religion and also contain foreign influences. Each person takes part in the Bathing Festival three times: at birth, at marriage, and at death. It is traditionally believed that people should not bathe casually, but only on the most important occasions.

Art

Tibetan art is deeply religious in nature, from the exquisitely detailed statues found in Gompas to wooden carvings and the intricate designs of the Thangka paintings. Tibetan art can be found in almost every object and every aspect of daily life.

Thangka paintings, a syncretism of Indian scroll-painting with Nepalese and Kashmiri painting, appeared in Tibet around the 8th century. Rectangular and painted on cotton or linen, they usually depict traditional motifs including religious, astrological, and theological subjects, and sometimes a mandala. To ensure that the image will not fade, organic and mineral pigments are added, and the painting is framed in colorful silk brocades.

Drama

The Tibetan folk opera, known as Ache lhamo, which literally means "sister goddess" or "celestial sister," is a combination of dances, chants and songs. The repertoire is drawn from Buddhist stories and Tibetan history.

Tibetan opera was founded in the fourteenth century by Thangthong Gyalpo, a lama and a bridge builder. Gyalpo, and seven girls he recruited, organized the first performance to raise funds for building bridges, which would facilitate transportation in Tibet. The tradition continued uninterrupted for nearly seven hundred years, and performances are held on various festive occasions such as the Lingka and Shoton festival. The performance is usually a drama, held on a barren stage that combines dances, chants, and songs. Colorful masks are sometimes worn to identify a character, with red symbolizing a king and yellow indicating deities and lamas. The performance starts with a stage purification and blessings. A narrator then sings a summary of the story, and the performance begins. Another ritual blessing is conducted at the end of the play. There are also many historical myths/epics written by high lamas about the reincarnation of a "chosen one" who will do great things.

Architecture

The most unusual feature of Tibetan architecture is that many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south. They are commonly made of a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth. Little fuel is available for heating or lighting, so flat roofs are built to conserve heat, and multiple windows are constructed to let in sunlight. Walls are usually sloped inwards at 10 degrees as a precaution against frequent earthquakes in the mountainous area. Tibetan homes and buildings are white-washed on the outside, and beautifully decorated inside.

Standing at 117 metres (384 ft) in height and 360 metres (1,180 ft) in width, the Potala Palace is considered the most important example of Tibetan architecture. Formerly the residence of the Dalai Lama, it contains over a thousand rooms within thirteen stories and houses portraits of the past Dalai Lamas and statues of the Buddha. It is divided between the outer White Palace, which serves as the administrative quarters, and the inner Red Quarters, which houses the assembly hall of the Lamas, chapels, 10,000 shrines, and a vast library of Buddhist scriptures.

Medicine

Tibetan medicine is one of the oldest forms in the world. It utilizes up to two thousand types of plants, forty animal species, and fifty minerals. One of the key figures in its development was the renowned 8th century physician Yutok Yonten Gonpo, who produced the Four Medical Tantras integrating material from the medical traditions of Persia, India and China. The tantras contained a total of 156 chapters in the form of Thangkas, which tell about the archaic Tibetan medicine and the essences of medicines in other places.

Yutok Yonten Gonpo's descendant, Yuthok Sarma Yonten Gonpo, further consolidated the tradition by adding eighteen medical works. One of his books includes paintings depicting the resetting of a broken bone. In addition, he compiled a set of anatomical pictures of internal organs.

Cuisine

The Cuisine of Tibet reflects the rich heritage of the country and people's adaptation to high altitude and religious culinary restrictions. The most important crop is barley. Dough made from barley flour, called tsampa, is the staple food of Tibet. This is either rolled into noodles or made into steamed dumplings called momos. Meat dishes are likely to be yak, goat, or mutton, often dried, or cooked into a spicy stew with potatoes. Mustard seed is cultivated in Tibet, and therefore features heavily in its cuisine. Yak yoghurt, butter and cheese are frequently eaten, and well-prepared yoghurt is considered something of a prestige item.

Clothing

Most Tibetans wear their hair long, although in recent times due to Chinese influence, some men do crop their hair short. The women plait their hair into two queues, the girls into a single queue.

Because of Tibet's cold weather, the men and women wear long thick dresses (chuba). The men wear a shorter version with pants underneath. The style of the clothing varies between regions. Nomads often wear thick sheepskin versions.

Literature

Tibet has national literature that has both religious, semi-spiritual and secular elements. While the religious texts are well-known, Tibet has the semi-spiritual Gesar Epic, which is the longest epic in the world and is enjoyed by people in Mongolia and Central Asia too. There are secular texts such as The Dispute Between Tea and Chang (Tibetan beer) and Khache Phalu's Advice.

Marriage customs

Polyandry is practiced in parts of Tibet. A typical arrangement is where a woman may marry male siblings. This is usually done to avoid division of property and provide financial security.[19] However, monogamy is more common throughout Tibet. Marriages are sometimes arranged by the parents, if the son or daughter has not picked their own partner by a certain age.

See also

- Limbu people

- Tibetan American

- Baltis

- Burig

- Monpa Tibetan

- Baima Tibetan

- Bhotias

Footnotes

- ↑ "China issues white paper on history, development of Xinjiang (Part One)". Xinhua. 2003-05-26. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2003-05/26/content_887226.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- ↑ Lewis, M. Paul (ed.), 2009. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/.

- ↑ Population transfer and control

- ↑ "1950—1990 年藏族人口规模变动及其地区差异研究" (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 2007-11-24. http://web.archive.org/web/20071124053818/http://www.tibetology.ac.cn/article2/ShowArticle.asp?ArticleID=2764.

- ↑ Fischer, Andrew M. (2008). "Has there been a decrease in the number of Tibetans since the peaceful liberation of Tibet in 1951?" In: Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China's 100 Questions, pp. 134, 136. Edited: Anne-Marie Blondeau and Katia Buffetrille. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24464-1 (cloth); 978-0-520-24928-8 (pbk).

- ↑ Tibetfrom the U.N. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific

- ↑ Barnett, Robert (2008). "People at the side of the Dalai Lama also said that the hospitals in Tibet only serve the Han people. Is that true?" In: Authenticating Tibet: Answers to China's 100 Questions, pp. 106-107. Edited: Anne-Marie Blondeau and Katia Buffetrille. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24464-1 (cloth); 978-0-520-24928-8 (pbk).

- ↑ Robert Barnett in Steve Lehman, The Tibetans: Struggle to Survive, Umbrage Editions, New York, 1998. pdf p.1

- ↑ "Special Blood allows Tibetans to live the high life." New Scientist. 3 November 2007, p. 19.

- ↑ "Elevated nitric oxide in blood is key to high altitude function for Tibetans." [1]

- ↑ "Tibetans Get Their Blood Flowing": http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2007/1029/2

- ↑ "Nitric oxide and cardiopulmonary hemodynamics in Tibetan highlanders": http://jap.physiology.org/cgi/content/full/99/5/1796

- ↑ Yi, Xin et al. (2010). "Sequencing of 50 Human Exomes Reveals Adaptation to High Altitude". Science (AAAS) 329 (5987): 75–78. doi:10.1126/science.1190371. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/sci;329/5987/75.

- ↑ University of California, Berkeley (1 July 2010). "Tibetans adapted to high altitude in less than 3,000 years". Press release. http://berkeley.edu/news/media/releases/2010/07/01_tibetan_genome.shtml. Retrieved 2010-07-03. "A comparison of the genomes of 50 Tibetans and 40 Han Chinese shows that ethnic Tibetans split off from the Han less than 3,000 years ago and since then rapidly evolved a unique ability to thrive at high altitudes and low oxygen levels."

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wade, Nicholas (July 1, 2010). "Scientists Cite Fastest Case of Human Evolution". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/02/science/02tibet.html. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- ↑ Stein (1972), p. 27.

- ↑ Su, Bing, et al. (2000)

- ↑ Stein, R.A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization. J.E. Stapleton Driver (trans.). Stanford University Press. pp. 28, 46.

- ↑ Stein (1978), pp. 97-98.

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Goldstein, Melvyn C., "Study of the Family structure in Tibet", Natural History, March 1987, 109-112 ([2] on the Internet Archive).

- Stein, R.A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization. J.E. Stapleton Driver (trans.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 (paper); ISBN 0-8047-0806-1.

- Su, Bing, et al. "Y chromosome haplotypes reveal prehistorical migrations to the Himalayas". Human Genetics 107, 2000: 582–590.

External links

- Modern Tibetan people from TravelChinaGuide.com

- Imaging Everest: Article on Tibetan people at the time of early mountaineering from the Royal Geographical Society

- Tibetan costume from china.org.cn (in English)

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||